Week 03 - EVAC and Evaluate

Thinking up of a game was not easy and refining it to something enjoyable and playable was even harder. The most challenging task was determining what angle we wanted to go for our game. We were quick to choose a cooperative game, but finding an activity that would encourage everyone to work together and feel motivated to reach the goal presented other issues. If we wanted a game that would “[make] things happen that none of you could do on your own” (Macklin and Sharp Ch. 3), everyone needed either the same goal or have roles with the same amount of importance.

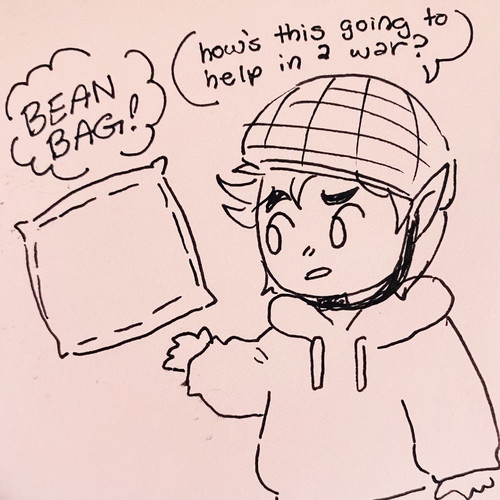

I definitely think giving our game a theme made this step easier. Since we had a story to play off of, people helping each other escape a battle zone, all we needed was a method to express it. The easiest way to address that would be giving everyone a basic task—like tossing a beanbag and taking a step towards the goal—but we couldn’t find a reason for anyone to complete the ask other than being told to do it. Instead, we chose to give our players a challenge as incentive.

Setting a winning condition meant we could “provide meaningful effort toward the game’s goal” (Macklin and Sharp Ch. 2). We deliberated on separate teams trying to achieve the same goal. We tried making one person the leader that everyone would run towards. We even contemplated the formation of the field to play on. Ultimately, the most fun we had during testing was letting everyone play along with the same role, so no person felt left out and responsibility was equally spread around whoever joined in.

Constraints were one of the best tools I think we utilized, as well. Described as “the limitations we put on players through the design of the actions, objects, and playspace of a game,” (Macklin and Sharp Ch. 2), setting restrictions added a level of depth to our design. Here, we added strict, limited ways the players could move before and after catching the beanbag. Our game at this point had an objective to complete and roadblocks that the players had to work around.

All of this, of course, had to lead back to the idea of having fun. If the game wasn’t fun and light-hearted, then we were missing the whole point of the project. Once the challenge and constraints were settled, we looked for way to give the players more autonomy. We needed to give them choices on how to proceed to engage them.

“A well-designed game provides feedback on player actions” (Macklin and Sharp Ch. 2). As we watched our game get played again and again, we watched different strategies emerge. Sometimes we were more cooperative, other times the best course of action was going solo. These were both valid ways to play, and both should be incentivized. This is likely why we implemented the consequence for dropping the bean bag and how to recover from that blunder. We gave the players more options for how to act and engage. Suddenly, there was more thought behind who to toss to and how to make the game successful that purely relied on player input.

Overall, I feel I better understand the thought process to designing a game, and I feel more confident going into the next project. Listening to the different games everyone created also showed me that there’s so many avenues to go down when designing!

Designing for Play Log - Kat

| Status | Prototype |

| Category | Other |

| Author | FrostyKatto |

More posts

- Week 09 - Shuffle and RepeatDec 04, 2021

- Week 11 - Yoochube Let's PlayNov 08, 2021

- Week 10 - A Balanced BreakfastNov 01, 2021

- Week 08 - Plants Vs. ZombiesOct 18, 2021

- Week 07 - Always Booyah! BackOct 11, 2021

- Week 06 - Improvise, Adapt, OvercomeOct 04, 2021

- Week 05 - Competitive ConcertsSep 27, 2021

- Week 04 - Point, Set, MatchSep 20, 2021

- Week 02 - New Games, Old TraditionsSep 06, 2021

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.